It’s no secret that modern tennis has long become a game played almost exclusively at the baseline. The reasons for this shift have been noted and discussed many times: changes in racket technology and efforts to slow down courts are the big two factors.

A majority of hard courts and grass were made to play slower; carpet became phased out entirely. More rallies = more entertainment was the underlying philosophy behind it all.

In the modern game, serve and volley as a play style, not just a tactic in the arsenal, is almost entirely dead. On the ATP you can find Maxime Cressy who managed to find some success in the top 100 two years ago but has since vanished from relevance.

The only woman I’ve seen actually serve and volley even a single point to my memory in the last several years is Karolina Muchova whose impeccable technique makes it somewhat viable. Slim pickings, huh.

Look at the top of the ATP and WTA right now and you will find a lot of players defined by their excellence from the baseline.

Daniil Medvedev, Jannik Sinner, Alexander Zverev, Iga Swiatek, Elena Rybakina, Jessica Pegula, the list goes on. Finding any of these players at the net is a surprise perhaps even to them with how lost some of them can look volleying.

And yet, despite this constant aversion to coming forward and constant pull towards the back of the court, the net remains a crucial part of modern tennis.

Even when everything is played out on the baseline, being able to volley and play at the net has become a valuable asset.

Variety more generally has become the answer to pure baseline tennis, the counterplay in the rock-paper-scissors of tennis tactics. I often use Medvedev as an example of this, a player in someways the final form of a defensive baseliner.

So much of his success from 2019 onwards has been in his defensive style that breaks opponents down from the back of the court. He’s a wall, he cannot be out rallied or hit through, so what do you do?

The answer most people point to is to come to the net or use drop shots to bring him forward, stop him being able to absorb everything from the back of the court.

The issue that for a long time the players around Medvedev didn’t have the tools to be able to prey on his weaknesses.

Players like Andrey Rublev, and for a period Sinner, struggle(d) so much with Medvedev because they too were rooted to the baseline with the same high powered high margin groundstrokes and nothing more.

In a game of baseline tennis, Medvedev wins. The problem for the Russian has become players that do have the ability to break out of that attrition.

Almost three years ago now Novak Djokovic turned to the serve and volley against him in the final of the Paris Masters event and has never looked back.

Carlos Alcaraz’s precise drop shots and volleying ability has similarly given him a comfortable time. Tennis has become all about baseline domination, but the very best still are those who can use variety and the net to their advantage.

Both US Open singles finals this year were defined by their baseline play, both in prevalence but also in the counterplay around it (or lack thereof).

The men’s final between Taylor Fritz and Sinner was a battle of two similar, high margin aggressive baseliners. Sinner won out in a comfortable three sets by the virtue of the fact that in such a matchup, anything Fritz can do he can do better.

Fritz could not hit through Sinner, nor could he out rally him in a battle of consistency. The American’s lack of variety outside of his big forehands and solid backhands killed his chances.

It’s no surprise that his one opening in the match where he broke at 3-3 in the third set came when he used a drop shot into a lob combo and then a net approach on consecutive points.

Tennis is a game played at the baseline, but to some extent the match was won (and lost) in the net game.

The women’s final was somewhat similar in terms of its focus on baseline exchanges, but it also highlighted the way in which eventual champion Aryna Sabalenka has evolved and rounded out her game over the course of 2024.

Sabalenka is a power player. She has a big serve and hits hard, heavy groundstrokes off both wings. She doesn’t want to rally much; every shot is going for the kill whether it’s crosscourt or down the line. There is no “neutral” Sabalenka ball.

It could be easy to think of Sabalenka’s game as something of a sledgehammer; brute force compared to more subtle approaches. But I think that would do a disservice to her and the way in which she has incorporated that sought after variety.

The big shift in Sabalenka’s game this year has been the introduction of the drop shot which entirely changes the dynamic of a point and offers a lot of options to her game that she has greatly benefited from. These new tactics were on full display in this final against Pegula.

The match was baseline heavy with Sabalenka wanting to assert herself in points and attack, her American opponent absorbing pace and challenging her with great depth of shot, consistency and redirection.

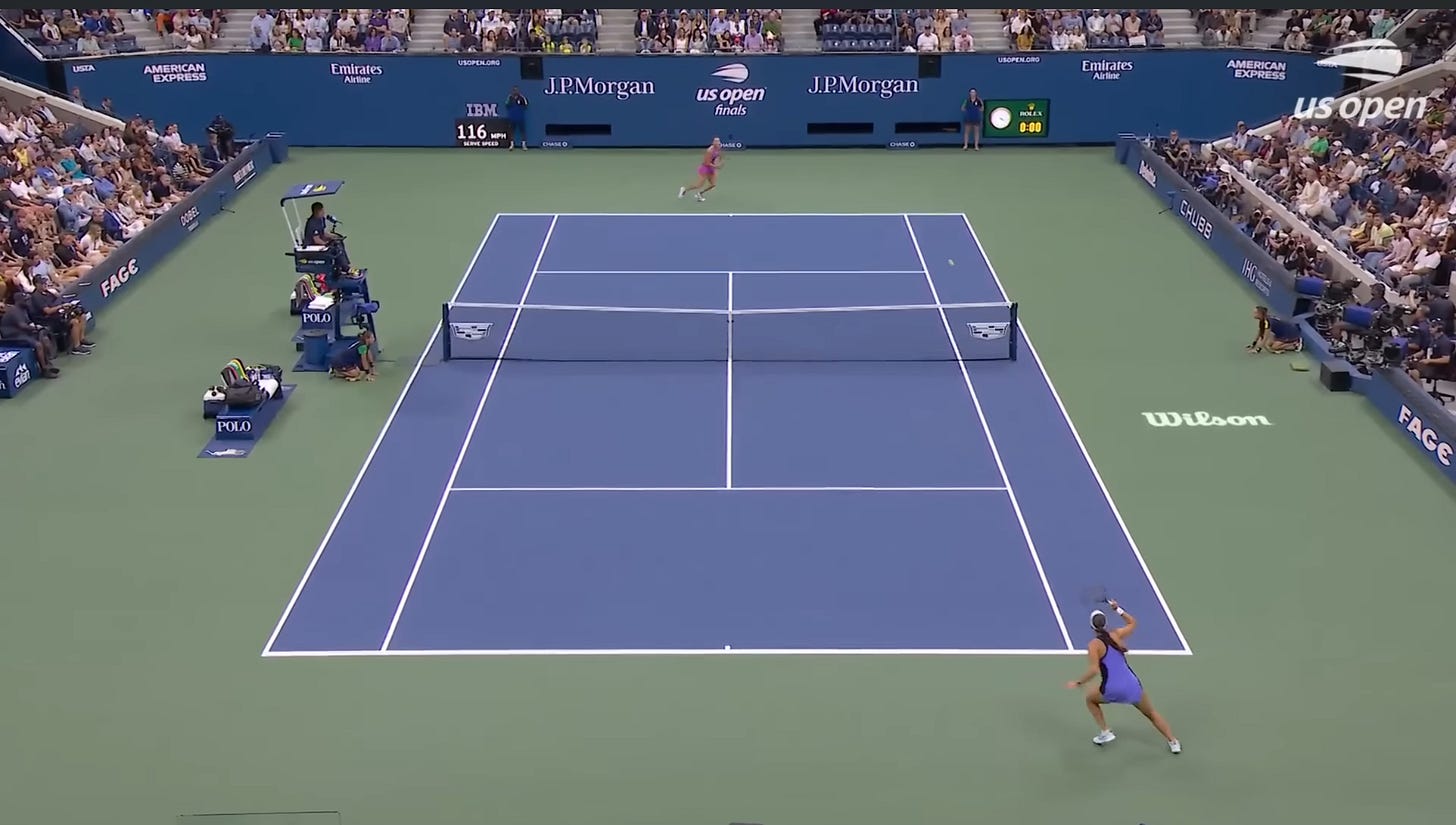

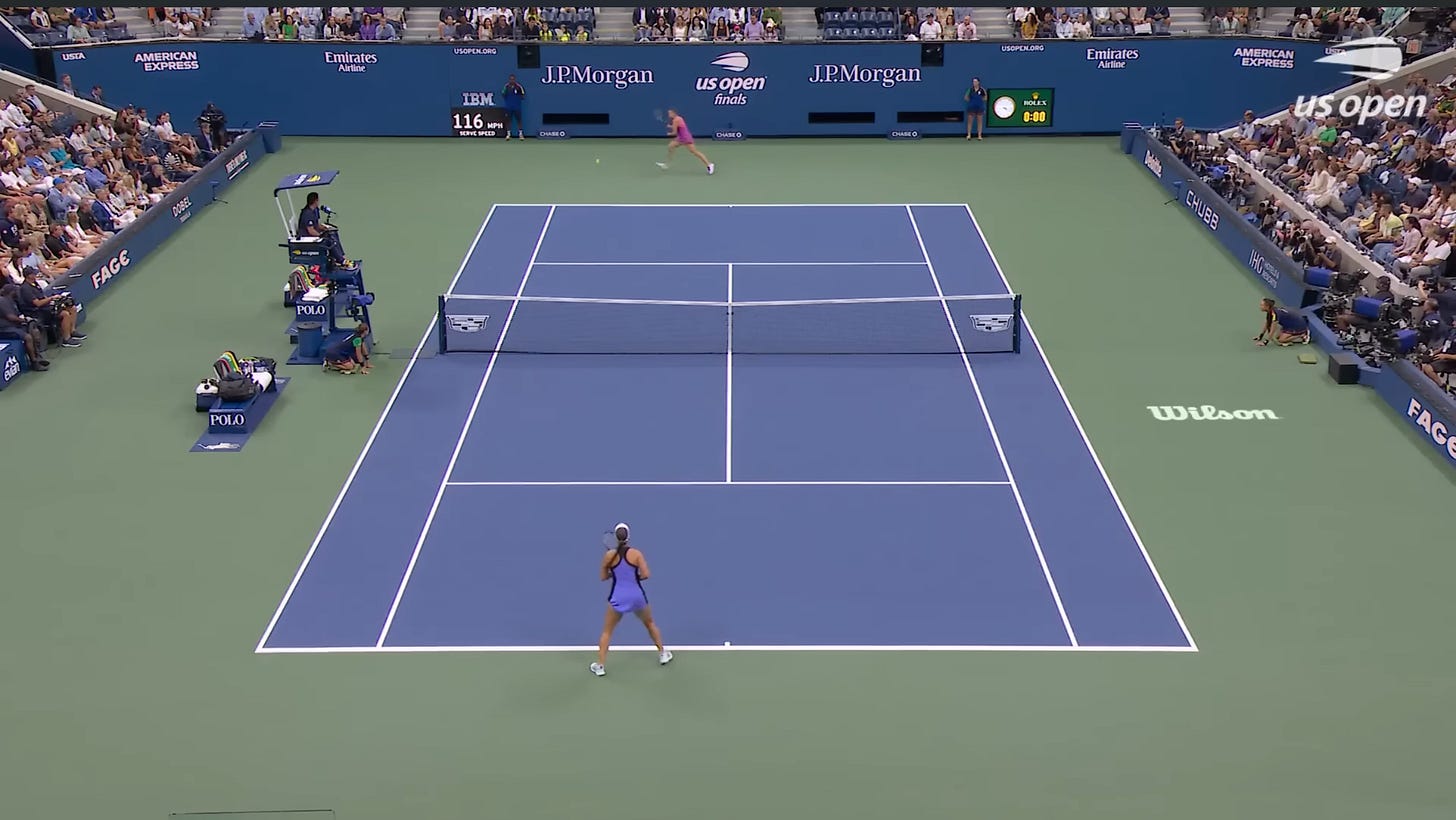

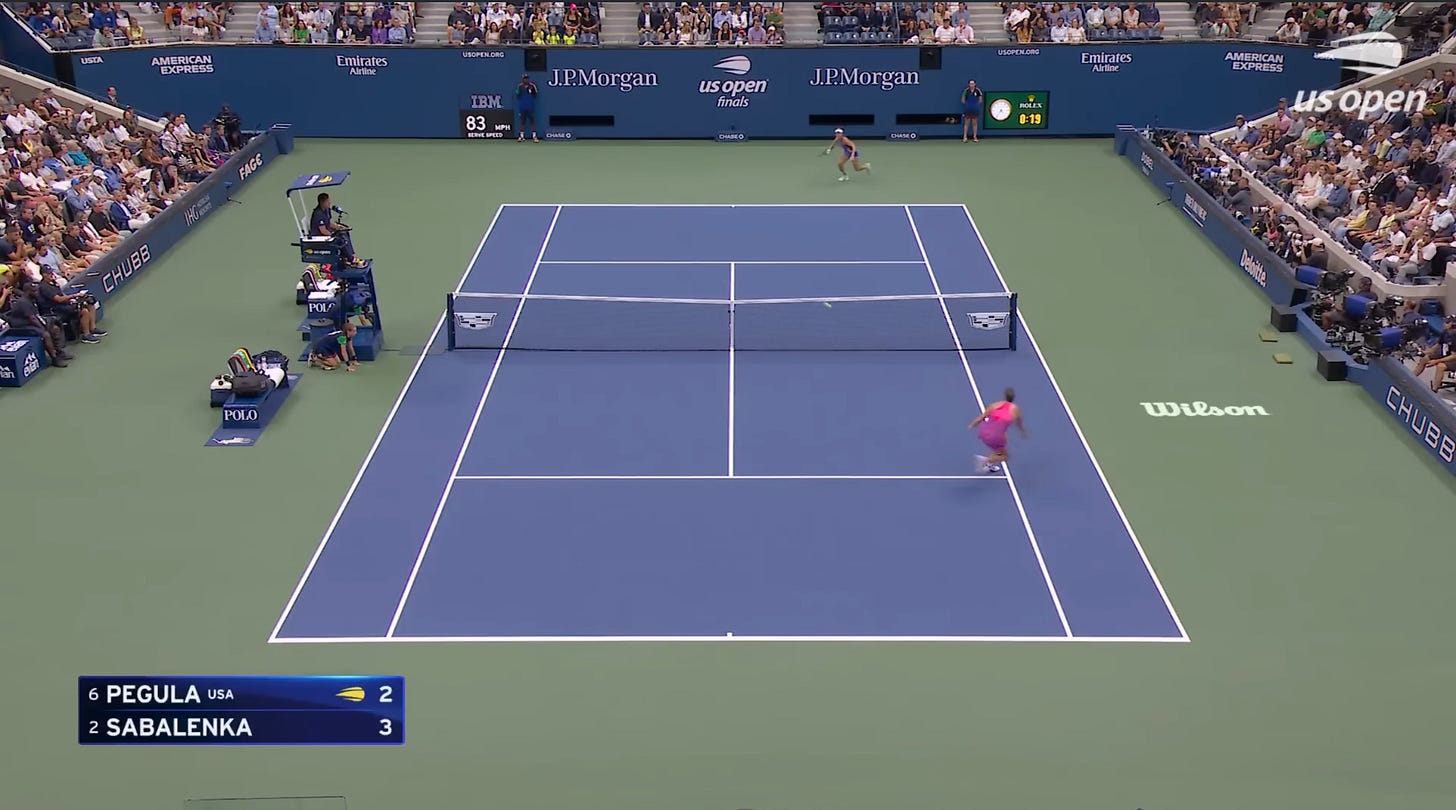

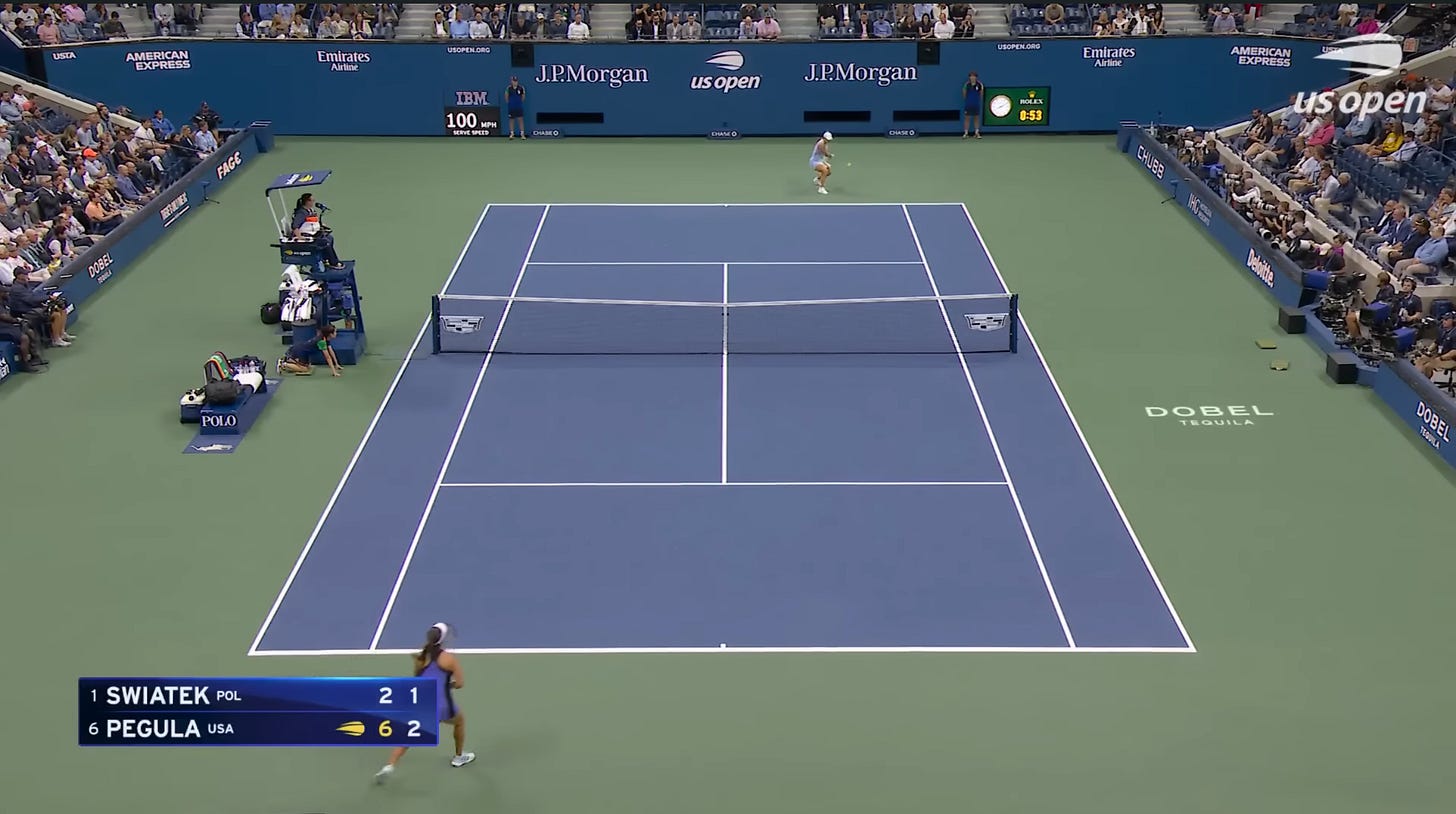

The battle lines were set in the very first point, won by Pegula. Sabalenka, top of the picture, fires a cross court forehand at Pegula who masterfully redirects it down the line, catching the Belarussian off guard.

Sabalenka gets the ball back, but it sits up in the middle of the baseline for Pegula to dictate, able to fire another forehand down the left line of the court for a clean winner.

There are plenty of points from this match showing punch-counterpunch, but there was also a fair share of something more attritional from Pegula.

She was able to keep points on her terms at times with cross-court exchanges, her depth stopping Sabalenka take control.

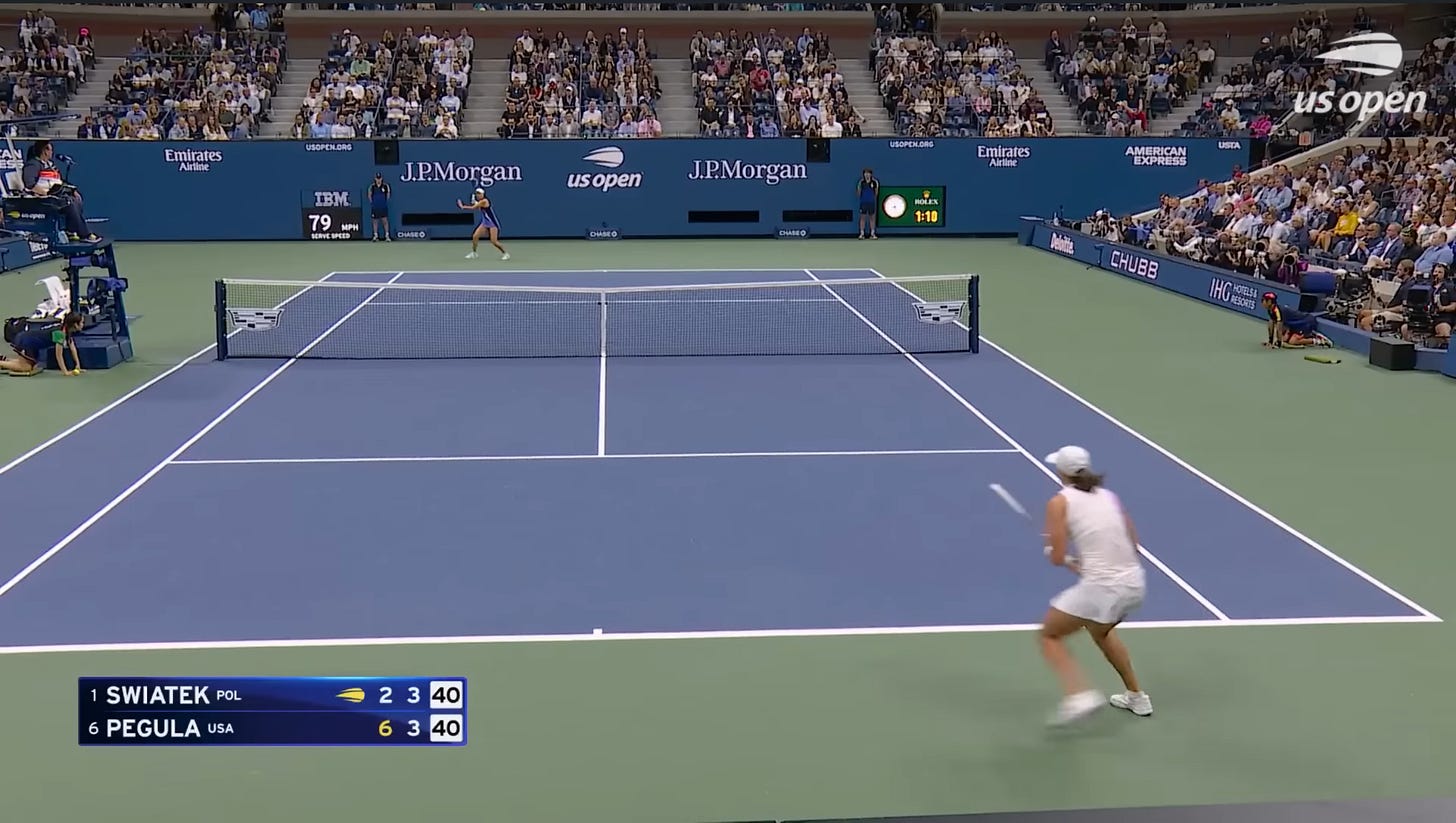

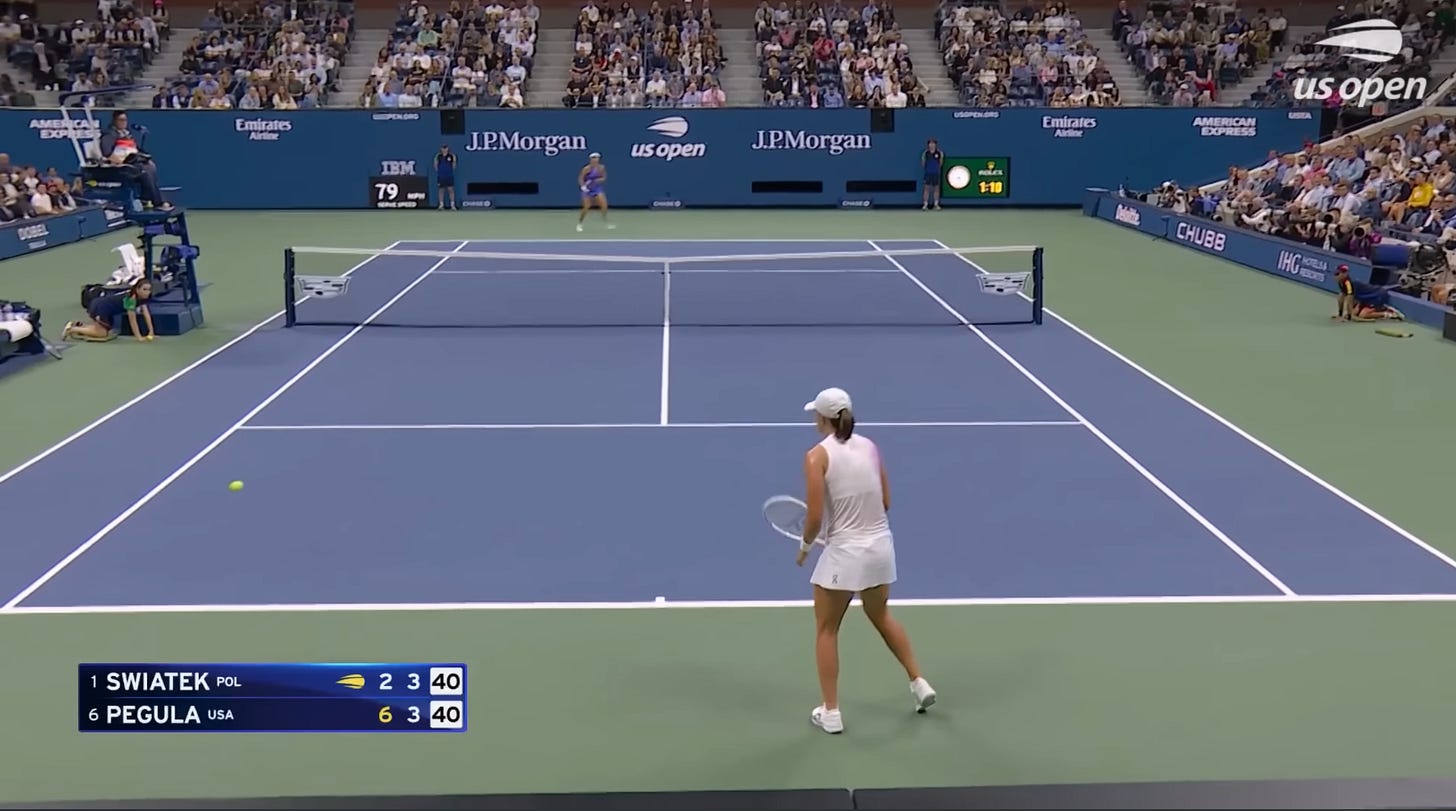

This is Pegula’s bread and butter. You can see similar dynamics in her win over the world number one Iga Swiatek in the quarterfinal, able to lock her into the cross-court exchange and force an error or change direction at will.

Sabalenka has numerous ways to get out of this dynamic, however. Obviously, she can use her immense power and precise aggression to catch Pegula out, dragging her out of position.

If you can consistently keep the ball in court despite the high-risk play, then you’ll do pretty well. The consistency and power also give Pegula a challenge in being able to stand up to that weight of shot and match it for an extended period of time.

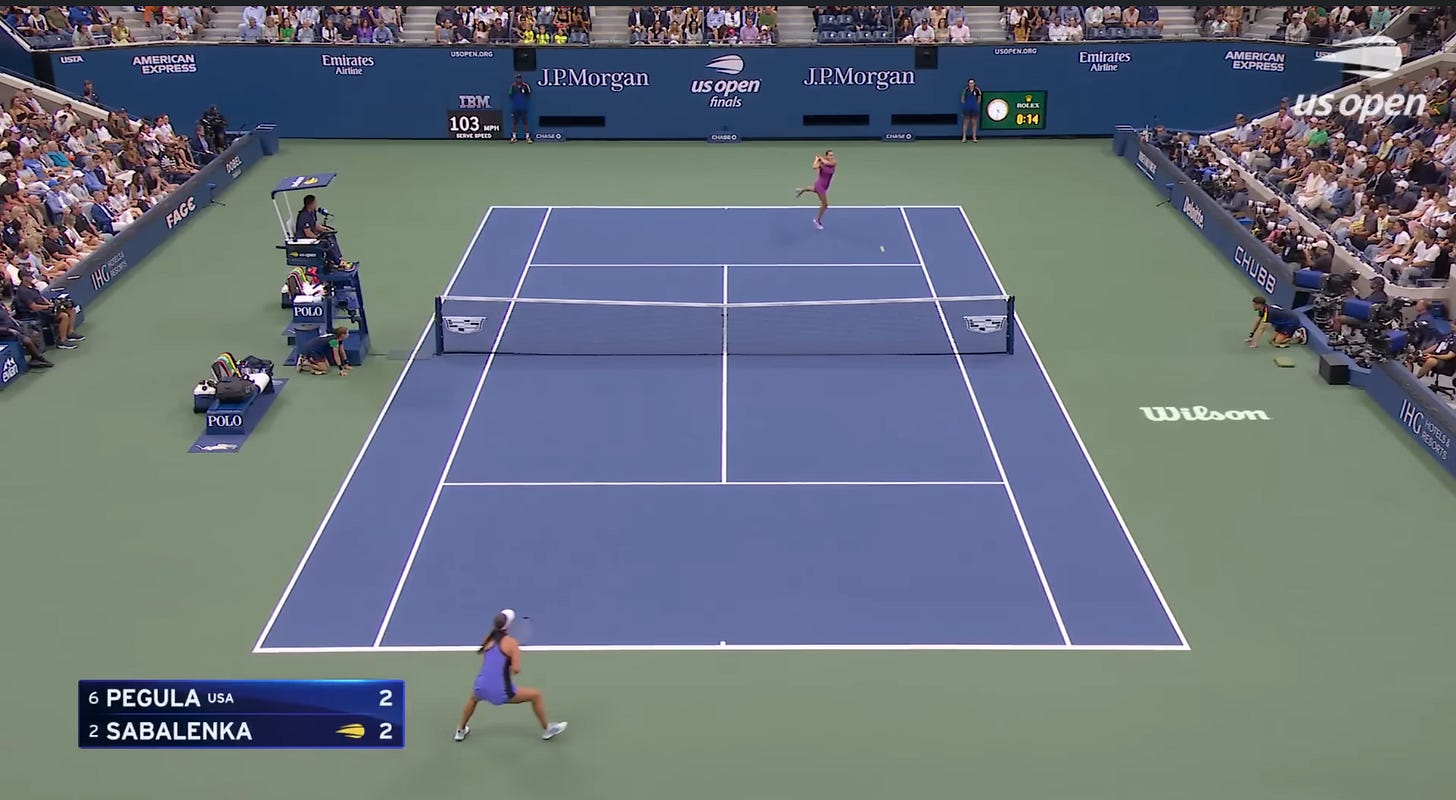

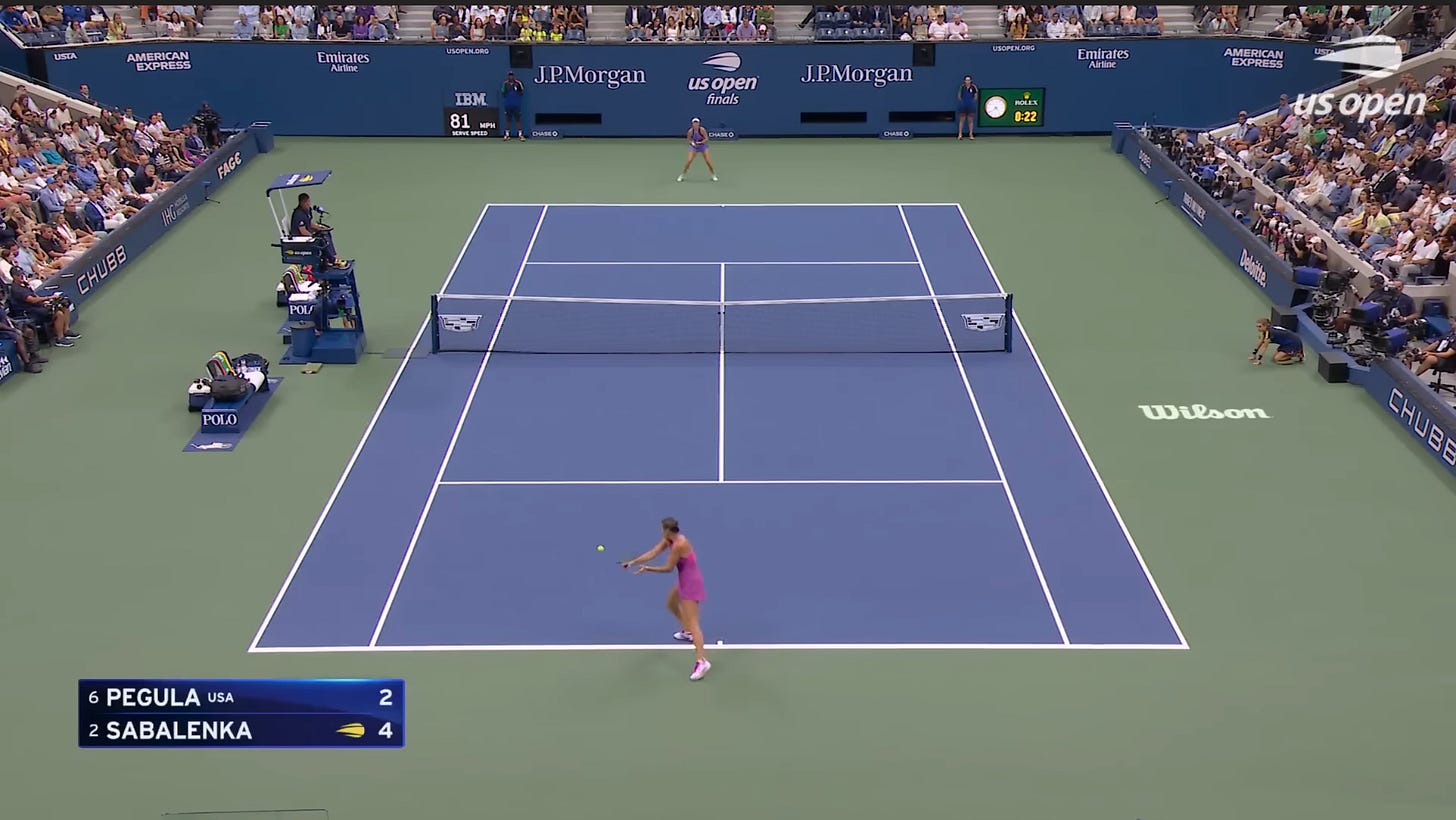

But Sabalenka also got consistent joy out of coming forward and using the net. We can see this early in the first set with her aggression when sending a shot down the line.

Sabalenka is stepping inside the court as she swings, sensing the opportunity to come forward when Pegula has so much ground to make up. Pegula can only stagger to the ball and get it up for a lob which Sabalenka is perfectly positioned to easily put away.

Sabalenka’s sense for approaching the net was on point throughout the match.

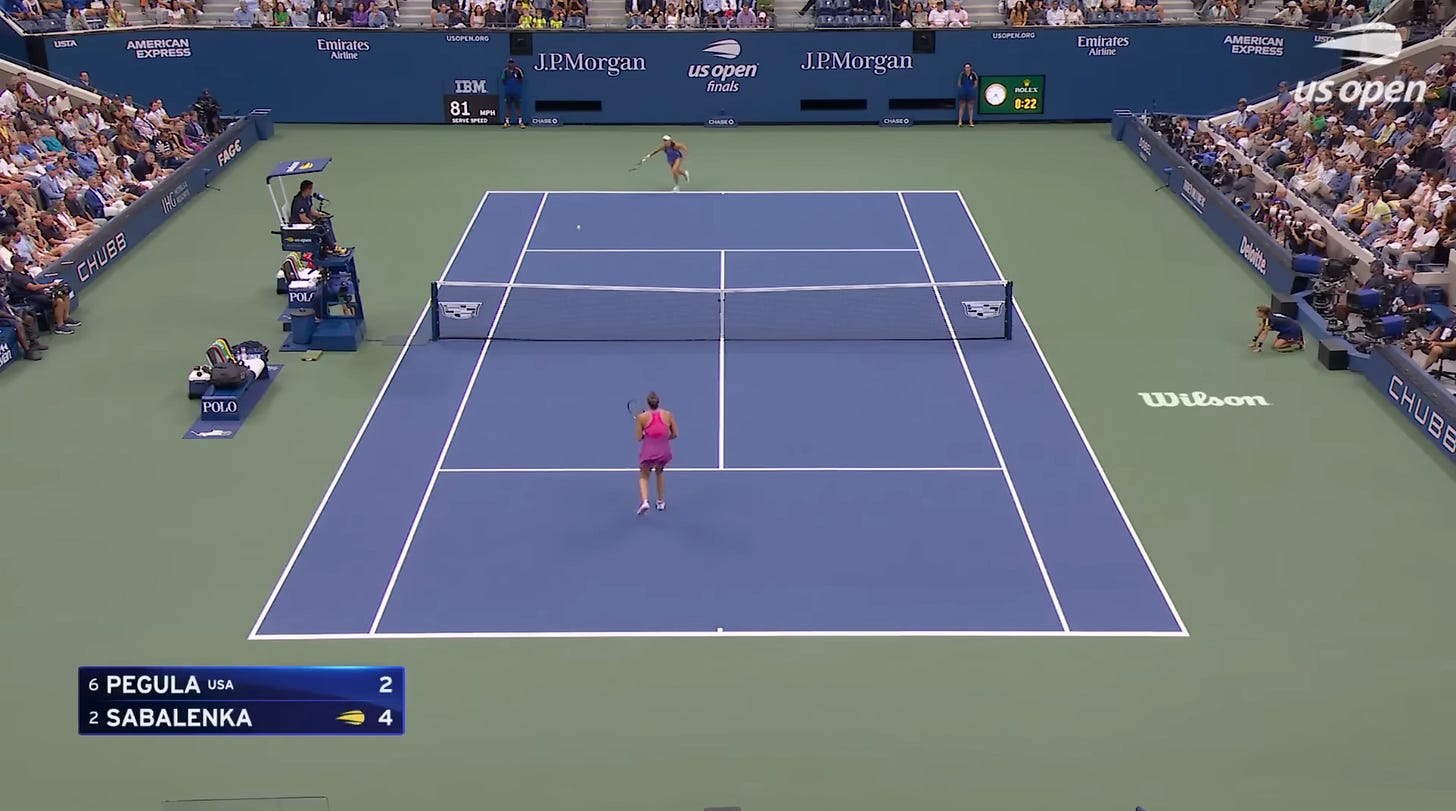

Here’s another example from the first set. Sabalenka fires a shot to Pegula’s backhand which she knows will get her on the run and immediately sets off to the net again with the American staggered.

Her volley when at the net is nicely executed, going cross-court landing in the left service box. Pegula’s options are totally cut off, she has no chance of getting to the ball.

This transition is in some ways a natural consequence of Sabalenka’s style; these high-risk, aggressive shots put her opponent immediately on the backfoot, of course she would come into the baseline from that.

But Sabalenka matches this with shots that “thread the needle” more, such as her drop shots.

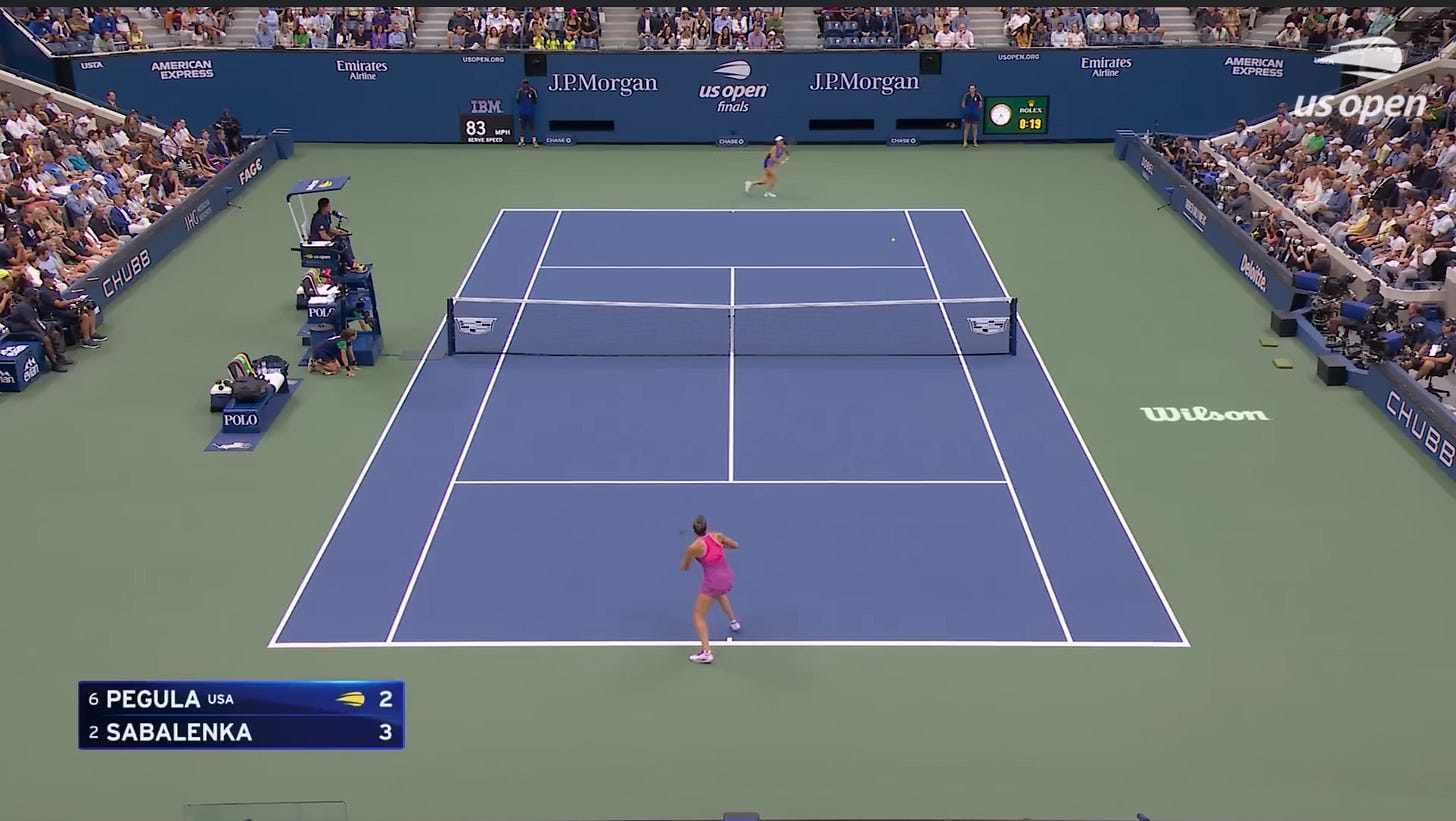

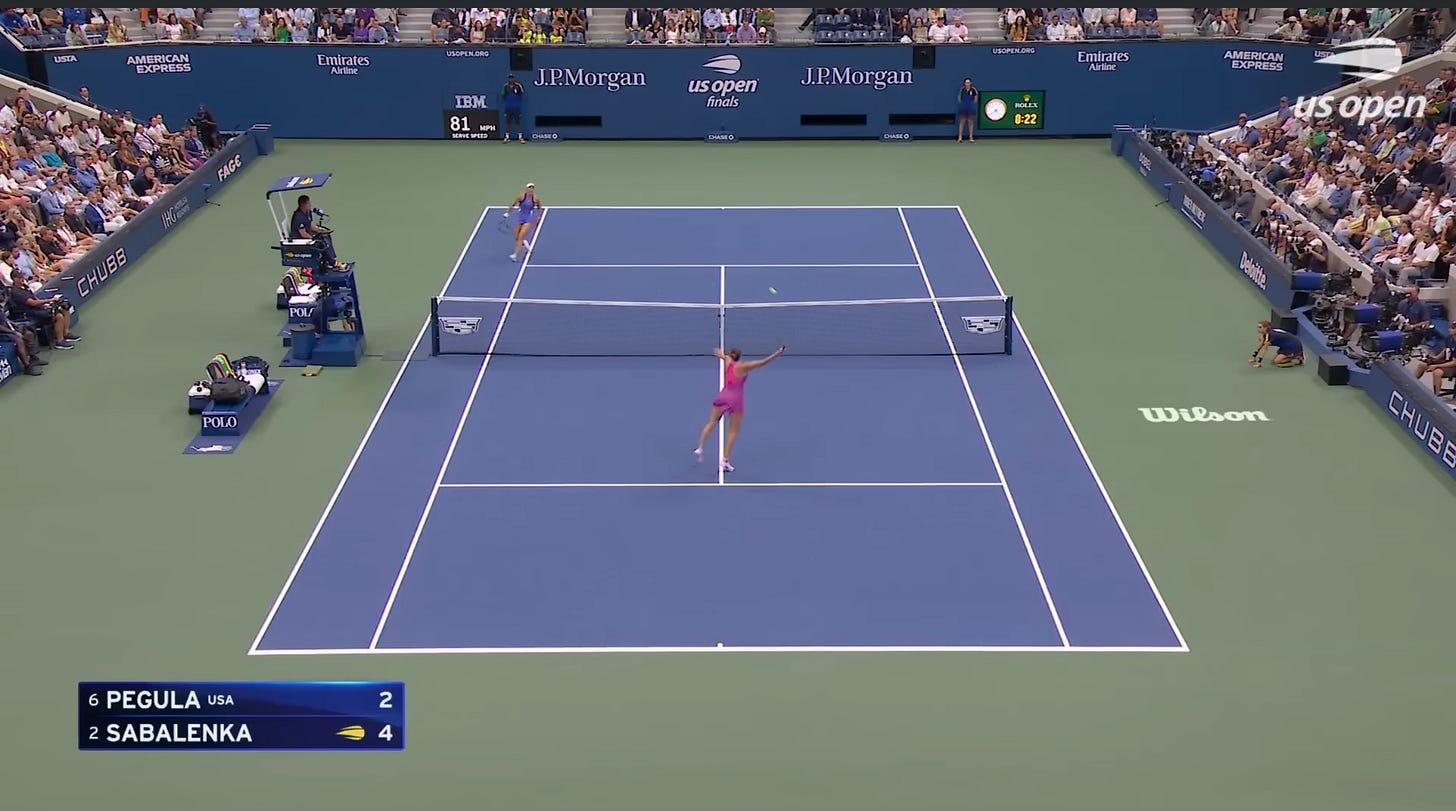

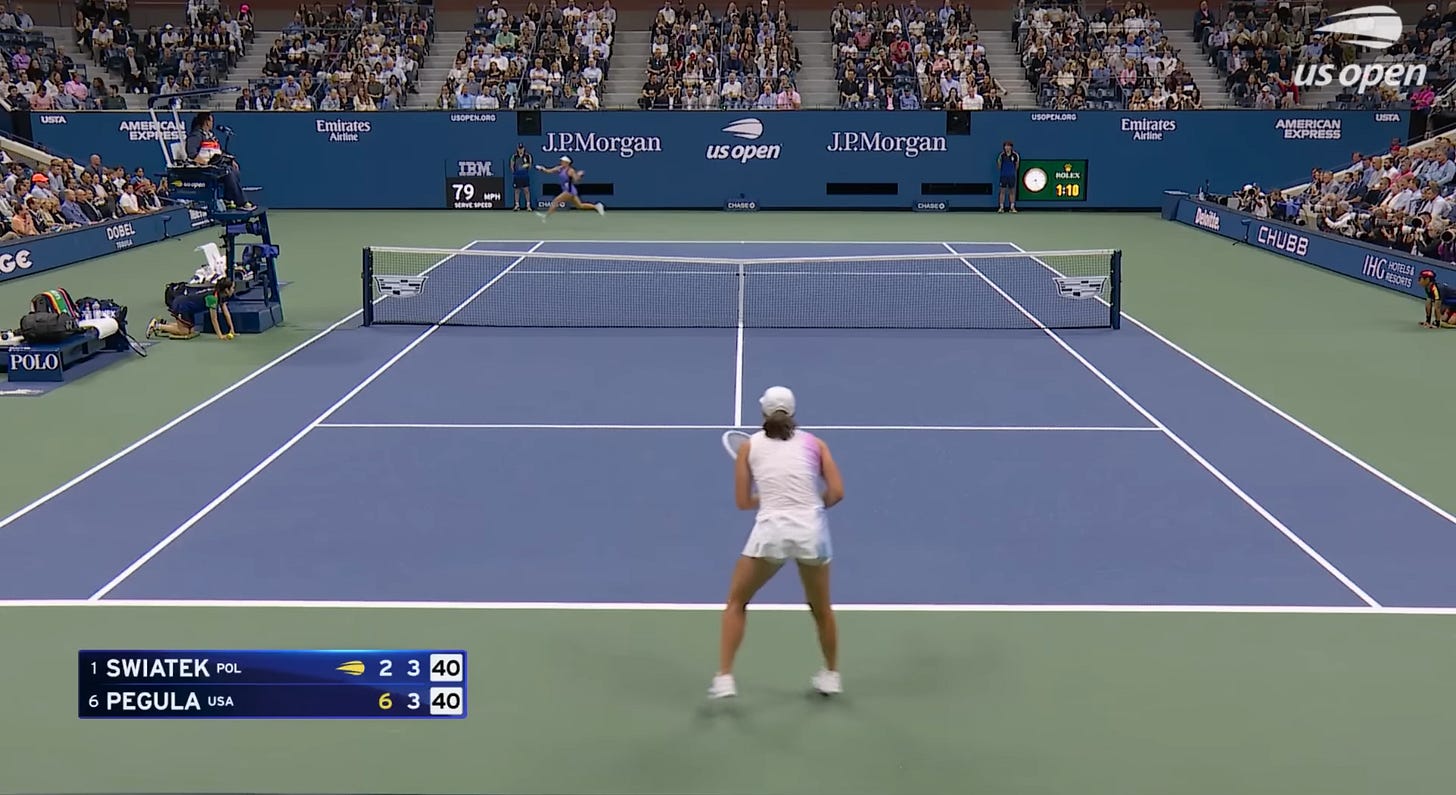

Here both players are stood in the middle of the baseline, Sabalenka could easily go with a backhand cross-court or down the line here, but instead she opts for the drop shot to bring Pegula forward.

This once again catches Pegula out, who is forced to scramble to the ball…

What’s key to me here is what Sabalenka does after the drop shot.

Look at how she comes forward immediately after playing it. She locks off Pegula’s options here. Pegula now has to hit a compromised shot regardless, but now the execution needs to be perfect to get past Sabalenka.

She can go line or cross-court, but both can be easily picked off. The attempt to carry the ball cross-court gives Sabalenka an easy put away at the net (sensing a pattern?).

Of course, the net play and drop shots are particularly effective against Pegula because of the American’s movement.

Pegula is an excellent defender (in the pure tennis, ball-striking sense) and has good movement back-and-forth across the baseline, but Sabalenka exposed her weaker diagonal and forward movement.

One might be cynical and suggest that it’s her opponent’s weaknesses making the tactics look more impressive than they might otherwise. However, this tactic feels pertinent when you compare it to Pegula’s match against Swiatek.

Sabalenka and Swiatek’s matches against Pegula were dominated at the baseline, but they highlight how variety (or the lack of it) can be so helpful in changing the dynamics of a match.

Swiatek’s match had similar patterns in being pegged back to deep baseline exchanges but was similarly able to work openings and opportunities much like Sabalenka.

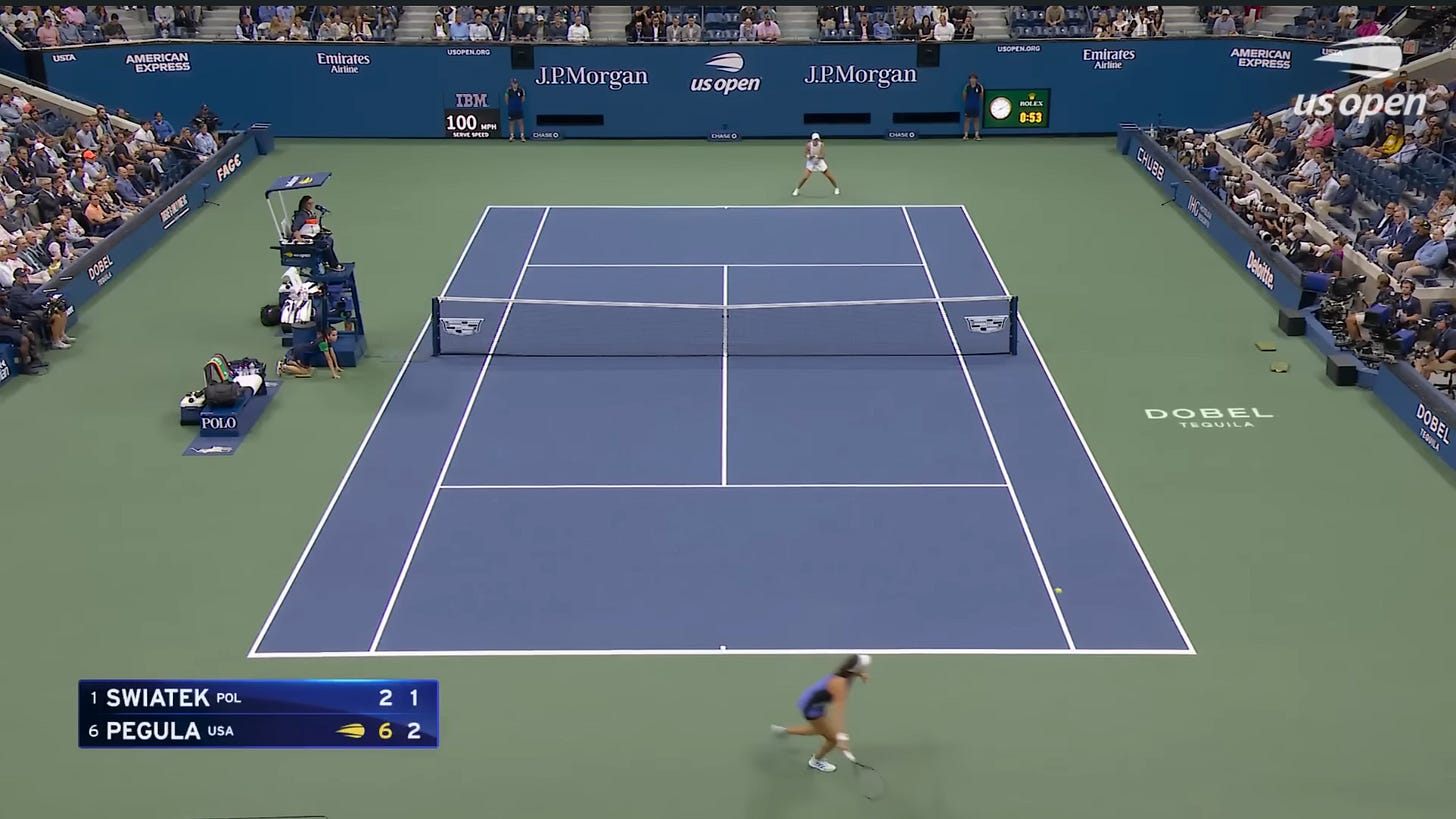

The difference in the second set of that match, however, was her rigidity to the baseline which helped Pegula. Take this point for example where Swiatek has worked a chance to attack with a backhand down the line.

It’s almost identical to Sabalenka’s backhand down the line we looked at before- Pegula’s even further away this time. It similarly has Pegula on the run, forced into a defensive lob…

But look at Swiatek’s positioning: she’s rooted to the baseline. This means Pegula’s lob can’t be taken out of the air like Sabalenka did so effortlessly.

Now look what Pegula’s gained from the lob. She’s reset the rally, Swiatek is behind the baseline to take it on, Pegula is in the middle of the baseline to start the exchange over. All the advantage of that attacking backhand has been lost.

Pegula loses this point off a backhand down the line error, but she still managed to extend it and get herself into it from what should have been an unwinnable position.

Now, to Swiatek’s credit, there were times she stepped inside the baseline to take on a smash to deal with Pegula’s lobs, but she was often stuck in these attritional battles at the baseline unable to get out.

A comparison to Sabalenka is to some extent comparing apples to oranges, because there are different players with different styles, but there is a valid comparison to be drawn.

Against an extremely consistent baseliner who can match their groundstrokes for depth and quality, they both have to find ways in which to control and dictate points.

Now, Sabalenka has an easier time by far on a fast hard court, but she also turned to these alternative tactics where required.

What could Swiatek do with her current game? Not much else, it seems. She was pinned back on her forehand side rarely able to do much beyond hit it back at Pegula which allowed the American to dictate and change direction when she wanted.

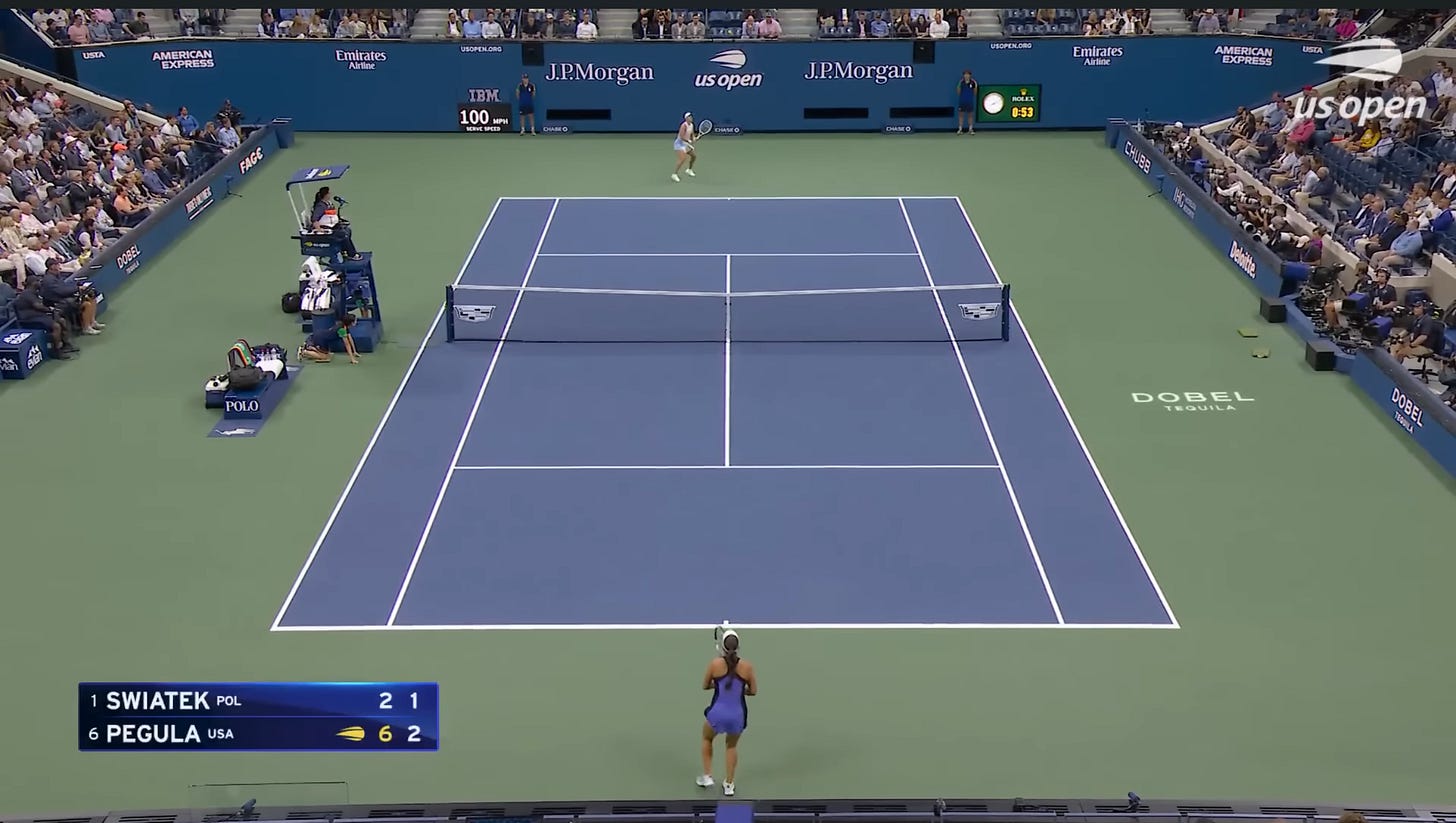

Here’s an example where Swiatek forces Pegula into a running cross court forehand.

She responds with another cross-court forehand which allows Pegula to hit a clean winner down the line.

It’s very similar to the opening point of the final; a Pegula forehand down the line to punish a cross-court ball from her opponent. Pegula got more joy out of this here than she did against Sabalenka.

Both Swiatek and Sabalenka were able to work Pegula out wide, getting her on the defensive, but only one of them could consistently convert these advantages.

Swiatek’s inability to transition to the net consistently or use any other shots outside of her standard forehand and backhand limited her options in the matchup. She couldn’t exploit any of Pegula’s weaknesses.

Swiatek had a lot of issues in that match- low first serve percentage, uncharacteristic unforced errors- but she struggled more with Pegula because her opponent can increasingly match her at the baseline.

Of course, we can still put an asterisk Swiatek-Sabalenka comparisons. It is somewhat unfair to compare the best fast hard-court player in the world to a player who is most exposed in these conditions.

Sabalenka was still able to win points reliably from the baseline because in these conditions it’s so difficult to force her off the baseline or cope with the power and precision coming at you.

But I still think it remains true that her game has evolved from pure baseline tennis. She has that variety to call upon and in a grand slam final she called upon it to great success.

The issue for Swiatek is that she can’t dictate as easily in fast conditions and is prone to being rushed more often. In slower conditions her measured aggression can be so much more effective because no one can break out of her point construction that moves them around.1

If she’s more exposed from the baseline in faster conditions, why not…move away from the baseline? At times it feels as if Swiatek is being forced to win long rallies on every point to either outlast an opponent or fashion a winner.

It is doable at times because she is the best player in the world, but it requires such an impeccable consistency and for her forehand to hold up for large periods. It’s not always sustainable and puts so much pressure on her.

If nothing else, Sabalenka’s net charges and drop shots can relief pressure in that she isn’t needing to rely on out rallying Pegula for an entire game.

Both of these women can dominate from the back of the court. But when an opponent can begin to match that baseline excellence, the B plan of the drop shot and net play offers a way out.

Sabalenka’s variety has also be great help in her weaker conditions. You’ll find a great showcase in her match against Elina Svitolina in Rome where she extensively used the drop shot to win points with her back against the wall including when match point down.

On a cold night on clay in May, some of the slowest conditions you’ll find on tour, the Belarussian couldn’t rely on her power to hit through the court. She had to find other ways to win.

Similarly, on fast courts where she can’t freely dictate as easily, Swiatek needs to find other ways to win. She doesn’t have those tools right now.

If nothing else, Sabalenka is a blueprint Swiatek can follow in how a player can add to their toolkit and the benefits it can provide. More options are never a bad thing.

Both these players might still play 70, 80, 90 percent of points at the baseline, but that small portion at the net can be crucial. When Swiatek isn’t able to totally dominate from the baseline, she has nowhere else to go. Sabalenka does.

Tennis is a game played at the baseline, but to some extent matches are won (and lost) in the net game.

It’s important not to oversell Sabalenka’s evolution but also not to underrate it. She primarily dictates from the baseline, but she is also now able to turn to the net for free points that aren’t built on huge groundstrokes or painting lines.

Despite the prevalence of baseline rallies, modern players at the elite level still need to flesh out their net play to be able to compete and win at the highest level.

It was a key development for both Rafael Nadal and Novak Djokovic in their careers, albeit implemented at different stages.

Even Sinner, the most Djokovic-like player on the ATP in his manner of high-margin baseline tennis, has started to incorporate a drop shot into his game more.

Tennis is dominated by points from the back of the court, but being able to move forward remains a crucial part of the game. Both US Open finals showed us why.

Taylor Fritz’s inability to consistent come to the net to make up for his disadvantage at the back of the court cost him. Aryna Sabalenka use of the net exposed her opponent and helped her ease to a third grand slam title.

Whether her rival Iga Swiatek can catch up to her on grass and faster hard courts is in some part a question of being able to expand the horizons of her own game and move forward beyond the baseline.

For more on Swiatek’s game and her point construction, I recommend my article on her from back in April on Popcorn Tennis: https://popcorntennis.com/2024/05/04/good-results-bad-process/